Understanding the impact of childhood trauma

The topic of childhood trauma is a difficult one to discuss. Not only is it confronting to consider children’s experience of trauma and abuse but naturally this topic can be triggering for many adults too. Yet it’s important that those who work with children have an understanding of the many, complex ways in which trauma can present and feel empowered to help.

While many children experience upsetting and frightening events, the term ‘childhood trauma’ most commonly refers to relational trauma – the experience of a caregiving relationship as frightening, abusive or unresponsive. Sadly, many young children experience abuse, neglect and family violence within their homes, which can be further complicated by a parents’ mental illness or substance use. In these situations, young children are doubly affected – not only by the traumatic incidents themselves, but by the lack of healthy supportive caregiving relationships, critical for healthy early development.

To know how best to help, it’s important that we first understand the impact that trauma has on children. Unfortunately, there’s no simple formula for predicting this. Instead, we consider the complex interplay between several factors.

These factors include the nature, severity and duration of the trauma, the temperament of the child and the level of support and quality of any other relationships available to the child. There are also other factors to consider too. Was the child exposed to drugs or alcohol while in the womb? What was the extent of any physical injuries or nutritional deficiencies experienced? Consider too the degree of financial hardship felt by the family since this factor, like many others, will further influence a child’s outcomes.

Age matters too of course. During the first year of life, important brain pathways develop making the first 12 months a particularly critical period. When infants experience trauma during this period, the impact tends to be much greater.

Given how many different factors are at play, it makes sense then that the effects of trauma can vary too.

These effects include:

- delays or difficulties relating to a child’s overall development

- poor concentration

- difficulties with learning

- impaired cognitive capacity

- poor social skills

Children will also often find it hard to calm down from big feelings states and may have come to rely on physical strategies such as rocking or head banging. They may find it difficult to problem solve or to control their impulses.

It helps to understand too that children who have been maltreated often never reach a totally calm state and may instead always be on the look out for danger.

Because they’re often on edge, children can find transitions particularly hard to deal with and may over-react to seemingly minor changes in their routine or environment.

These kids may struggle to ‘read’ others’ facial expressions and intentions and will often experience difficulties relating to their behaviour.

Children who have experienced early trauma also often develop what we call a ‘negative internal working model’ – that is, they may have learned to see themselves as unlovable/ unworthy, others as rejecting or unavailable and the world as unsafe. And these differences in how they see themselves, others and the world will naturally influence how they interpret various situations and, importantly, how they choose to respond.

Of course, the earlier we get in to help, the better. It’s critical that we ensure children’s current safety and that children and their carers are linked in with professional support services. That said, educators can do a lot to help too.

I cover these practical healing strategies in detail in my webinar series for early years educators but the foundation for all of these approaches is for educators to build strong positive relationships with children. This really is the key to helping children heal. This is where things first went wrong and is the most important place to start when setting things right. Once we have this foundation, we can start to address any of the important developmental tasks or skills that a child may not have gained but they first need to feel safe and accepted by us in order to learn these.

Of course, many children will benefit from ongoing professional therapeutic support but the ideal goal is for carers, educators and therapists to work together so that they can each contribute to the child’s recovery. Educators are in a particularly powerful position to help through their continuing, daily interactions. When children experience a safe, predictable, nurturing relationship with an adult who accepts and understands them, they can start to see themselves as lovable, others as reliable and the world as mostly safe. And their healing can begin…

You can watch Dr Kaylene Henderson talk more on this important topic in this Storypark video:

To learn specific strategies for helping children heal from childhood trauma, educators can register for Dr Kaylene Henderson’s Webinar here.

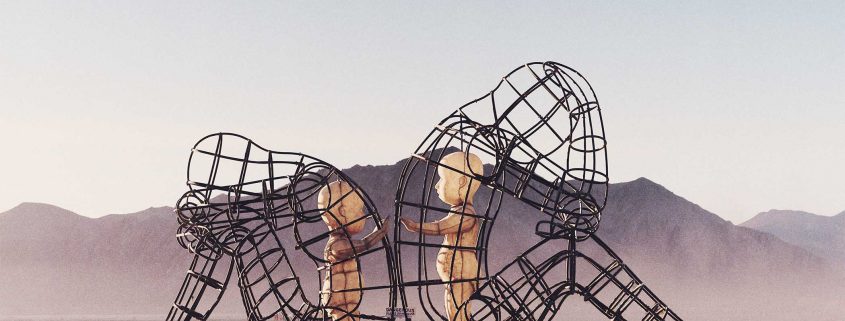

(Image credit: Gerome Viavant; Sculpture by Alexander Milov;)